First there was Detroit, and now there’s Flint. After more or less staying under the radar for over a year, in the last few weeks the water crisis has become national news. The overall story is pretty clear. Back in April 2014, the city stopped getting its water from the system that serves the Detroit metropolitan area, which it had been doing since 1967, and switched over to the Flint River instead. Residents immediately noticed the difference, complaining about the water’s taste, smell, and color. City and state officials ignored or dismissed them, insisting that the water was safe—and trying to hide evidence to the contrary. In fact, the corrosive river water had caused lead in the city’s aging pipes to leach into the water supply. A year and a half after switching to the Flint River, the proportion of children with above-average levels of lead in their blood had doubled. All of the children in Flint now have to be treated for lead exposure. In the same period, an abrupt spike in a rare, waterborne illness called Legionnaire’s Disease caused 87 infections and at least ten deaths. Late last week, Governor Rick Snyder finally declared a state of emergency and requested federal aid.

The main approach that’s been used on the left to understand and analyze the Flint water crisis is the “shock doctrine,” which foregrounds democracy (or the lack thereof) as the key analytical category for explaining what went wrong. This phrase was coined by the activist and writer Naomi Klein in her 2007 book of the same name to refer to the techniques used by neoliberal politicians to implement austerity policies. Since these measures are so unpopular, Klein argued, they can’t be put in place through normal, democratic means. Instead, opportunistic politicians take advantage of situations of emergency, when the public is distracted and no alternatives are readily available, to force them through without contestation. One of Klein’s best examples is the package of sweeping education reforms imposed in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, which basically privatized the city’s public schools overnight.

Today, Michigan is probably the state where the shock doctrine framework is most applicable. For more than decade now, Michigan governors have been appointing so-called “emergency managers” (EMs) to run school districts and cities for which a “state of financial emergency” has been declared. These unelected administrators rule by fiat—they can override local elected officials, break union contracts, and sell off public assets and privatize public functions at will. It’s not incidental that the vast majority of the people who have lived under emergency management are black. Flint, whose population was 55.6% black as of the 2010 census (in a state whose population is 14.2% black overall), was under emergency management from December 2011 to April 2015. As noted above, it was during that period that the decision was made to stop purchasing water from Detroit and start drawing water directly from the Flint River.

Much of the commentary on the situation in Flint has focused on the emergency manager, and consequently the water crisis appears as a struggle that is being played out on the political terrain. Liberals see the problem as rooted in electoral politics—since Governor Snyder appointed Flint’s emergency managers, the source of the problem are the Republicans and their right-wing, corporate sponsors. They forget that Democrats have also appointed emergency managers. In any case, it’s harder than it seems to identify the responsible party here. It was one of Flint’s emergency managers who eventually made the decision to tap the Flint River, but it was after the city’s elected officials took the first key step, with the city council initially approving the switch away from Detroit in an overwhelming 7-1 vote back in March 2013. At a June 2013 meeting that included Flint city officials, representatives from the Genesee County Drain Commission, and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, the determination was made that the Flint River would be “more difficult to treat” but was nevertheless a “viable” source. Officials at multiple levels of government (city, county, and state) and across multiple jurisdictions played a role. The amount of ink that’s been spilled trying to figure out who’s responsible underscores the diffuse character of the structures of governance through which these decisions are made.

More importantly, what’s missing from this line of analysis is an acknowledgment of the structural shift in the global economy beginning in the 1960s and intensifying through the 70s and 80s. This brings us to a second approach to what’s happening in Flint, which frames the crisis through the lens of “disposability.” The deindustrialization of manufacturing cities like Flint and Detroit—first with suburbanization, relocating factories to segregated white suburbs, then with offshoring, relocating factories to other regions of the global economy—has had material impacts that are relatively insulated from political decision-making, especially at the city level. In Flint, notes historian Andrew Highsmith, GM’s workforce declined from more than 80,000 in 1955 to less than 8,000 by 2009 (pp. 2-5). As production was relocated and productivity increased, sectors of the working class have been rendered permanently superfluous to the needs of capital, and are expelled from the labor process, waged employment, and, increasingly, from what remains of the welfare state.

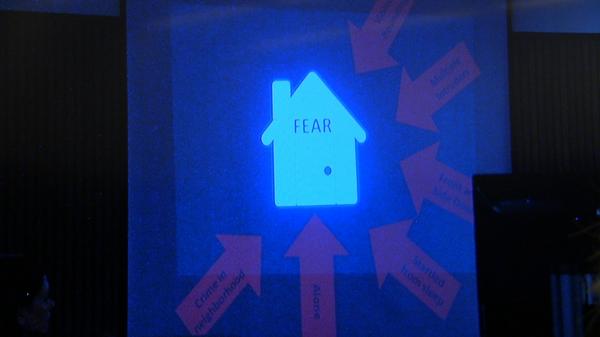

The result is a growing surplus population for which the state must deploy new forms of control. This has led, most obviously, to the massive expansion of policing and incarceration since the 1970s. But a second process, which has received significantly less attention, has also occurred in parallel to this one: the removal, withholding, or control of infrastructural systems and services—like education, health, and, of course, water—that are necessary for the reproduction of communities. In a recent article, Rada Katsarova and Jon Cramer analyze this second means of control in the context of the battle over the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department:

In the last decade, especially after the 2008 financial crisis, the urban centers of the Midwest such as Chicago and Detroit, but also in the Northeast, such as Baltimore and Philadelphia, have developed a new dynamic: the use of the state (in the form of local or regional governments) to transfer infrastructural resources and their control out of or away from marginalized urban populations, which are predominantly black, brown, and immigrant. These infrastructures range from health and educational resources to natural and civic resources such as water and sewage systems. There has been a tendency to read these battles around infrastructure as just another round of neoliberalism—another example of the “shrinking state.” Such an approach, however, seems unable to grasp how these infrastructural grabs, rather than a consequence of the state shrinking, are in fact a distinct kind of raced and classed resource transfer mobilized and sanctioned by the state. Nowhere is this clearer than in Detroit, where the predominantly white suburbs succeeded under the cover of Detroit’s 2013-14 bankruptcy proceedings to pry the possession of the water and sewage infrastructure away from the city proper. Not only have the mostly African-American residents of the city lost control of these infrastructures, they now have to subsidize the social reproduction of the predominantly white, wealthier Detroit suburbs.

Local, regional, and state governments are removing the basic, infrastructural supports that are necessary for the reproduction of life. As a consequence, residents of cities like Flint and Detroit, in particular black and immigrant populations, have been subjected to increasing vulnerability in forms like declining life expectancy and appalling infant mortality. “Disposability” and “surplus population” sound like abstract concepts, but they’re a tangible, visceral reality for folks on the ground in Flint. “We’re like disposable people here,” one resident told the Toronto Star the other day. “We’re not even human here, I guess.”

These disposable populations are raced. The geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore defines racism as “the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” What racism names, in other words, is not bias, prejudice, or discrimination, but the systems that orchestrate the siphoning of resources away from some populations and redirect them toward others. These systems do more than just define which lives matter and which lives don’t—they materially make some lives matter by killing others more. When a Flint resident tells the Detroit Free Press that “we get treated like we don’t matter,” the message is clear that to not matter is to slowly be killed.

Most of the time, slow death is hard to see. In individual cases, it can be difficult to perceive the gap between a death that comes at the “right” time and one that comes “too soon.” Disposable populations usually die gradually, with years quietly shaved off their life expectancies through such “accidents” as heart attacks, diabetes complications, and asthma. What is different about the water crisis in Flint is that slow death has suddenly become visible, traceable back to a single cause: the water.

The removal of infrastructures and services is, then, the right-hand of the carceral system: a means of disciplining disposable populations by inflicting slow deaths upon them. But this process is not new. It is relatively continuous with the long historical trajectory of what appears from this vantage point as a form of race war, by which white communities withdrew material support from and indeed plundered black communities, barricading themselves into suburban lives through segregation and policing and insulating these lives with resource transfers from the increasingly black population trapped within the city limits.

To give a specific example, Highsmith shows that the suburbanization of Flint’s manufacturing, and the corresponding withdrawal of tax dollars, was already getting underway by the 1950s. As companies like GM increasingly decentralized production, taking advantage of tax benefits at local and federal levels, they also sought out and acquired infrastructural supports from the municipality. “In order to operate their facilities,” he writes, “business managers from GM and other firms required sewers, large quantities of water, and other services that were often unavailable in suburbs and rural areas. Representatives from GM thus aggressively lobbied Flint’s city commissioners to extend water and sewer lines to their new suburban plants. By the close of the 1950s, their efforts had resulted in new water and sewer hookups for at least seven of GM’s suburban plants.” The city of Flint also subsidized suburban production through a stratified rate structure for water customers. Residential customers living within the city limits paid a relatively higher rate for smaller quantities of water (32 cents per hundred cubic feet of water up to 10,500 cubic feet), while industrial customers at suburban plants paid relatively lower rates for significantly larger quantities (20 cents per hundred cubic feet in excess of 105,000 cubic feet). “This policy, which rewarded the largest consumers of water with significantly lower rates, amounted to a large subsidy for local manufacturers,” one that was paid for by city residents, a population that was increasingly black (p. 130). (More recently, one of the early signs of the magnitude of the water crisis in Flint was GM’s decision in October 2014 to stop using the city’s water at its engine plant due to concern about corrosion. The warning went unheeded.)

The Flint water crisis is best seen as continuous with these histories of expropriation, rather than sharply differentiated from them by new political instruments like emergency management. In this sense, the “shock doctrine” framework misses something critical about the situation in Flint. Because it emphasizes the lack of democracy, this approach tends to foreground either the responsibility of individual politicians—the governor, the emergency manager, the head of the state’s environmental quality department—or, more helpfully, the emergency manager law as a whole. This is an important part of the story, and we’re all for getting rid of them. But the exit of any or all of these political figures, and even the elimination of emergency management, will not change the fact that racialized surplus populations will continue to inhabit cities like Flint, and that states will continue to manage and discipline them in one way or another. By foregrounding “disposability,” we are interested in thinking about what it would take to reproduce communities, or for communities to reproduce themselves, without relying on capital and the state, to create autonomous infrastructures of social reproduction that do not continuously subject black, immigrant, and marginalized white populations to premature death.